Sequoiadendron giganteum (giant sequoia; also known as giant redwood, Sierra redwood, Sierran redwood, California big tree, Wellingtonia or simply big tree—a nickname also used by John Muir[3]) is the sole living species in the genus Sequoiadendron, and one of three species of coniferoustreesknown as redwoods, classified in the family Cupressaceae in the subfamily Sequoioideae, together with Sequoia sempervirens (coast redwood) and Metasequoia glyptostroboides(dawn redwood). Giant sequoia specimens are the most massive trees on Earth.[4] The common use of the name sequoia usually refers to Sequoiadendron giganteum, which occurs naturally only in groves on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountain range of California.

The giant sequoia is listed as an endangered species by the IUCN, with fewer than 80,000 trees remaining. Since its last assessment as an endangered species in 2011, it was estimated that another 13–19% of the population (or 9,761–13,637 mature trees) was destroyed during the Castle Fire of 2020 and the KNP Complex & Windy Fire in 2021, events attributed to fire suppression, drought and global warming.[5] Despite their large size and adaptations to fire, giant sequoias have become severely threatened by a combination of fuel load from fire suppression, which fuels extremely destructive fires that are also exacerbated by drought and climate change. These conditions have led to the death of many populations in large fires in recent decades. Prescribed burns to reduce available fuel load may be crucial for saving the species.[6][7]

The etymology of the genus name has been presumed—initially in The Yosemite Book by Josiah Whitney in 1868[8]—to be in honor of Sequoyah (1767–1843), who was the inventor of the Cherokee syllabary.[9] An etymological study published in 2012 concluded that Austrian Stephen L. Endlicher is actually responsible for the name. A linguist and botanist, Endlicher corresponded with experts in the Cherokee language including Sequoyah, whom he admired. He also realized that coincidentally the genus could be described in Latin as sequi (meaning to follow) because the number of seeds per cone in the newly classified genus aligned in mathematical sequence with the other four genera in the suborder. Endlicher thus coined the name “Sequoia” as both a description of the tree’s genus and an honor to the indigenous man he admired.[10]

Description

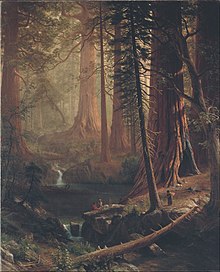

Giant sequoia specimens are the most massive individual trees in the world.[4] They grow to an average height of 50–85 m (164–279 ft) with trunk diameters ranging from 6–8 m (20–26 ft). Record trees have been measured at 94.8 m (311 ft) tall. Trunk diameters of 17 m (56 ft) have been claimed via research figures taken out of context.[11] The specimen known to have the greatest diameter at breast heightis the General Grant tree at 8.8 m (28.9 ft).[12]Between 2014 and 2016, it is claimed that specimens of coast redwood were found to have greater trunk diameters than all known giant sequoias – though this has not been independently verified or affirmed in any academic literature.[13] The trunks of coast redwoods taper at lower heights than those of giant sequoias which have more columnar trunks that maintain larger diameters to greater heights.

The oldest known giant sequoia is 3,200–3,266 years old based on dendrochronology.[14][15] Giant sequoias are among the oldest living organisms on Earth, and are the verified third longest-lived tree species after the Great Basin bristlecone pine and alerce. Giant sequoia bark is fibrous, furrowed, and may be 90 cm (3 ft) thick at the base of the columnar trunk. The sap contains tannic acid, which provides significant protection from fire damage.[16] The leaves are evergreen, awl-shaped, 3–6 mm (1⁄8–1⁄4 in) long, and arranged spirally on the shoots.

The giant sequoia regenerates by seed. The seed cones are 4–7 cm (1+1⁄2–3 in) long and mature in 18–20 months, though they typically remain green and closed for as long as 20 years. Each cone has 30–50 spirally arranged scales, with several seeds on each scale, giving an average of 230 seeds per cone. Seeds are dark brown, 4–5 mm (0.16–0.20 in) long, and 1 mm (0.04 in) broad, with a 1-millimeter (0.04 in) wide, yellow-brown wing along each side. Some seeds shed when the cone scales shrink during hot weather in late summer, but most are liberated by insect damage or when the cone dries from the heat of fire. Young trees start to bear cones after 12 years.

Trees may produce sprouts from their stumps subsequent to injury, until about 20 years old; however, shoots do not form on the stumps of mature trees as they do on coast redwoods. Giant sequoias of all ages may sprout from their boles when branches are lost to fire or breakage.

A large tree may have as many as 11,000 cones. Cone production is greatest in the upper portion of the canopy. A mature giant sequoia disperses an estimated 300–400 thousand seeds annually. The winged seeds may fly as far as 180 m (590 ft) from the parent tree.

Lower branches die readily from being shaded, but trees younger than 100 years retain most of their dead branches. Trunks of mature trees in groves are generally free of branches to a height of 20–50 m (70–160 ft), but solitary trees retain lower branches.

Distribution

The natural distribution of giant sequoias is restricted to a limited area of the western Sierra Nevada, California. As a paleoendemicspecies,[17] they occur in scattered groves, with a total of 81 groves (see list of sequoia groves for a full inventory), comprising a total area of only 144.16 km2 (35,620 acres). Nowhere does it grow in pure stands, although in a few small areas, stands do approach a pure condition. The northern two-thirds of its range, from the American River in Placer Countysouthward to the Kings River, has only eight disjunct groves. The remaining southern groves are concentrated between the Kings River and the Deer Creek Grove in southern Tulare County. Groves range in size from 12.4 km2 (3,100 acres) with 20,000 mature trees, to small groves with only six living trees. Many are protected in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks and Giant Sequoia National Monument.

The giant sequoia is usually found in a humid climate characterized by dry summers and snowy winters. Most giant sequoia groves are on granitic-based residual and alluvial soils. The elevation of the giant sequoia groves generally ranges from 1,400–2,000 m (4,600–6,600 ft) in the north, to 1,700–2,150 metres (5,580–7,050 ft) to the south. Giant sequoias generally occur on the south-facing sides of northern mountains, and on the northern faces of more southerly slopes.

High levels of reproduction are not necessary to maintain the present population levels. Few groves, however, have sufficient young trees to maintain the present density of mature giant sequoias for the future. The majority of giant sequoia groves are currently undergoing a gradual decline in density since European settlement.

Historic range

While the present day distribution of this species is limited to a small area of California, it was once much more widely distributed in prehistoric times, and was a reasonably common species in North American and Eurasian coniferous forests until its range was greatly reduced by the last ice age. Older fossil specimens reliably identified as giant sequoia have been found in Cretaceous era sediments from a number of sites in North America and Europe, and even as far afield as New Zealand[18] and Australia.[19]

Artificial groves

In 1974, a group of giant sequoias was planted by the United States Forest Service in the San Jacinto Mountains of Southern California in the immediate aftermath of a wildfire that left the landscape barren. The giant sequoias were rediscovered in 2008 by botanist Rudolf Schmid and his daughter Mena Schmidt while hiking on Black Mountain Trail through Hall Canyon. Black Mountain Grove is home to over 150 giant sequoias, some of which stand over 6.1 m (20 ft) tall. This grove is not to be confused with the Black Mountain Grove in the southern Sierra. Nearby Lake Fulmor Grove is home to seven giant sequoias, the largest of which is 20 m (66 ft) tall. The two groves are located approximately 175 mi (282 km) southeast of the southernmost naturally occurring giant sequoia grove, Deer Creek Grove.[20][21]

It was later discovered that the United States Forest Service had planted giant sequoias across Southern California. However, the giant sequoias of Black Mountain Grove and nearby Lake Fulmor Grove are the only ones known to be reproducing and propagating free of human intervention. The conditions of the San Jacinto Mountains mimic those of the Sierra Nevada, allowing the trees to naturally propagate throughout the canyon.[22]

Ecology

Giant sequoias are in many ways adapted to forest fires. Their bark is unusually fire resistant, and their cones will normally open immediately after a fire.[23] Giant sequoias are a pioneer species,[24] and are having difficulty reproducing in their original habitat (and very rarely reproduce in cultivation) due to the seeds only being able to grow successfully in full sun and in mineral-rich soils, free from competing vegetation. Although the seeds can germinate in moist needle humus in the spring, these seedlings will die as the duff dries in the summer. They therefore require periodic wildfire to clear competing vegetation and soil humus before successful regeneration can occur. Without fire, shade-loving species will crowd out young sequoia seedlings, and sequoia seeds will not germinate. When fully grown, these trees typically require large amounts of water and are therefore often concentrated near streams.[citation needed]Squirrels, chipmunks, finches and sparrows consume the freshly sprouted seedlings, preventing their growth.[25]

Fires also bring hot air high into the canopy via convection, which in turn dries and opens the cones. The subsequent release of large quantities of seeds coincides with the optimal postfire seedbed conditions. Loose ground ash may also act as a cover to protect the fallen seeds from ultraviolet radiation damage. Due to fire suppression efforts and livestock grazing during the early and mid-20th century, low-intensity fires no longer occurred naturally in many groves, and still do not occur in some groves today. The suppression of fires leads to ground fuel build-up and the dense growth of fire-sensitive white fir, which increases the risk of more intense fires that can use the firs as ladders to threaten mature giant sequoia crowns. Natural fires may also be important in keeping carpenter ants in check.[26] In 1970, the National Park Service began controlled burns of its groves to correct these problems. Current policies also allow natural fires to burn. One of these untamed burns severely damaged the second-largest tree in the world, the Washington tree, in September 2003, 45 days after the fire started. This damage made it unable to withstand the snowstorm of January 2005, leading to the collapse of over half the trunk.

In addition to fire, two animal agents also assist giant sequoia seed release. The more significant of the two is a longhorn beetle(Phymatodes nitidus) that lays eggs on the cones, into which the larvae then bore holes. Reduction of the vascular water supply to the cone scales allows the cones to dry and open for the seeds to fall. Cones damaged by the beetles during the summer will slowly open over the next several months. Some research indicates many cones, particularly higher in the crowns, may need to be partially dried by beetle damage before fire can fully open them. The other agent is the Douglas squirrel(Tamiasciurus douglasi) that gnaws on the fleshy green scales of younger cones. The squirrels are active year-round, and some seeds are dislodged and dropped as the cone is eaten.[27]

Genome

The genome of the giant sequoia was published in 2020. The size of the giant sequoia genome is 8.125 Gb (8.125 billion base pairs) which were assembled into eleven chromosome-scale scaffolds, the largest to date of any organism.[28][29]

This is the first genome sequenced in the Cupressaceae family, and it provides insights into disease resistance and survival for this robust species on a genetic basis. The genome was found to contain over 900 complete or partial predicted NLR genes used by plants to prevent the spread of infection by microbial pathogens.

The genome sequence was extracted from a single fertilized seed harvested from a 1,360-year-old tree specimen in Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Park identified as SEGI 21. It was sequenced over a three-year period by researchers at University of California, Davis, Johns Hopkins University, University of Connecticut, and Northern Arizona Universityand was supported by grants from Save the Redwoods League and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture as part of a species conservation, restoration and management effort.[30]

Discovery and naming

The giant sequoia was well known to Native American tribes living in its area. Native American names for the species include wawona, toos-pung-ish and hea-mi-withic, the latter two in the language of the Tule River Tribe.

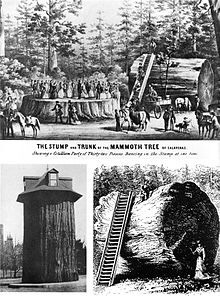

The first reference to the giant sequoia by Europeans is in 1833, in the diary of the explorer J. K. Leonard; the reference does not mention any locality, but his route would have taken him through the Calaveras Grove.[31]Leonard’s observation was not publicized. The next European to see the species was John M. Wooster, who carved his initials in the bark of the ‘Hercules’ tree in the Calaveras Grove in 1850; again, this observation received no publicity. Much more publicity was given to the “discovery” by Augustus T. Dowd of the Calaveras Grove in 1852, and this is commonly cited as the species’ discovery by non-natives.[31] The tree found by Dowd, christened the ‘Discovery Tree’, was felled in 1853.

The first scientific naming of the species was by John Lindley in December 1853, who named it Wellingtonia gigantea, without realizing this was an invalid name under the botanical codeas the name Wellingtonia had already been used earlier for another unrelated plant (Wellingtonia arnottiana in the family Sabiaceae). The name “Wellingtonia” has persisted in England as a common name.[32]The following year, Joseph Decaisnetransferred it to the same genus as the coast redwood, naming it Sequoia gigantea, but again this name was invalid, having been applied earlier (in 1847, by Endlicher) to the coast redwood. The name Washingtonia californica was also applied to it by Winslow in 1854, though this too is invalid, belonging to the palm genus Washingtonia.

In 1907, it was placed by Carl Ernst Otto Kuntzein the otherwise fossil genus Steinhauera, but doubt as to whether the giant sequoia is related to the fossil originally so named makes this name invalid.

The nomenclatural oversights were finally corrected in 1939 by John Theodore Buchholz, who also pointed out the giant sequoia is distinct from the coast redwood at the genus level and coined the name Sequoiadendron giganteum for it.

The etymology of the genus name has been presumed—initially in The Yosemite Book by Josiah Whitney in 1868[8]—to be in honor of Sequoyah (1767–1843), who was the inventor of the Cherokee syllabary.[9] An etymological study published in 2012, however, concluded that the name was more likely to have originated from the Latin sequi (meaning to follow) since the number of seeds per cone in the newly classified genus fell in mathematical sequence with the other four genera in the suborder.[10]

John Muir wrote of the species in about 1870:

“Do behold the King in his glory, King Sequoia! Behold! Behold! seems all I can say. Some time ago I left all for Sequoia and have been and am at his feet, fasting and praying for light, for is he not the greatest light in the woods, in the world? Where are such columns of sunshine, tangible, accessible, terrestrialized?’[33]

Uses

Wood from mature giant sequoias is highly resistant to decay, but due to being fibrous and brittle, it is generally unsuitable for construction. From the 1880s through the 1920s, logging took place in many groves in spite of marginal commercial returns. The Hume-Bennett Lumber Company was the last to harvest giant sequoia, going out of business in 1924.[35] Due to their weight and brittleness, trees would often shatter when they hit the ground, wasting much of the wood. Loggers attempted to cushion the impact by digging trenches and filling them with branches. Still, as little as 50% of the timber is estimated to have made it from groves to the mill. The wood was used mainly for shingles and fence posts, or even for matchsticks.

Pictures of the once majestic trees broken and abandoned in formerly pristine groves, and the thought of the giants put to such modest use, spurred the public outcry that caused most of the groves to be preserved as protected land. The public can visit an example of 1880s clear-cutting at Big Stump Grove near General Grant Grove. As late as the 1980s, some immature trees were logged in Sequoia National Forest, publicity of which helped lead to the creation of Giant Sequoia National Monument.[citation needed]

The wood from immature trees is less brittle, with recent tests on young plantation-grown trees showing it similar to coast redwood wood in quality. This is resulting in some interest in cultivating giant sequoia as a very high-yielding timber crop tree, both in California and also in parts of western Europe, where it may grow more efficiently than coast redwoods. In the northwest United States, some entrepreneurs have also begun growing giant sequoias for Christmas trees. Besides these attempts at tree farming, the principal economic uses for giant sequoia today are tourism and horticulture.

Leave a Reply